Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. By Jonny Steinberg for The Times:

By Jonny Steinberg for The Times:

A couple of years ago, two journalist friends of mine spent an afternoon with Oscar Pistorius. For much of the time, they recall, Oscar was quiet and self-contained. Then, apropos of nothing, he told a story.

He was driving on the outskirts of a black township, he said, when a dog ran under his wheels. In his rear-view mirror, he watched as it dragged itself off the road by its front legs, its hind legs useless to it now. Its back was clearly broken. He stopped and got out of his car to find the dog’s owner had come out on to the street, shouting, cursing. What to do? Oscar grabbed his gun, shot the dog and drove off.

On Valentine’s Day 2013, when the world learned that Oscar had shot Reeva Steenkamp dead through a closed bathroom door, this story no longer sounded the same. Before February 14, the man in the tale my friends tell is a little inscrutable, too hard perhaps, and clearly a cowboy. In the end, though, he does use his gun to put an animal out of its misery. But now, along with everything else Oscar has ever said and done, it takes its place in the biographical backdrop to an alleged murder.

So it is with all the crazy tales about Oscar. They are legendary. Versions of them appeared periodically in the New York Times, in Wired, in New Scientist. The journalist arrives in Johannesburg to find that Oscar himself has come to the airport to meet him. There is no chauffeur; Oscar will drive. On the freeway, he clocks 250km/h while reading a text message from a girl who wants to spend the night with him. The journalist is scared; he suddenly remembers that last year Oscar almost killed himself in a speedboat accident.

Another such tale: at Oscar’s home, talk turns to guns and Oscar grabs his 9mm pistol and two boxes of ammunition. Now Oscar and the journalist are burning a trail to the firing range, because Oscar insists on teaching the journalist to shoot.

Before February 14, these were colourful trimmings of magazine profiles. Oscar’s accomplishments were superhuman. He had licence to be a little crazy. Indeed, it was expected. But now a switch has flipped and we are listening to these same stories in a very dark place.

Something odd happened to South Africa when news of Steenkamp’s death broke. By nightfall, the billboards of Oscar had been removed. South Africa, which had loved Oscar unreservedly that morning, now hated him. As it spat venom at Oscar, so it excoriated itself. In newspapers and on radio and TV, South Africans kept confusing Oscar with the whole nation. Oscar was a symptom, it was said, of too many guns, of too much crime, of too much fear. He was a sign men were out of control, that they were killing, beating and raping the women they ostensibly loved. Oscar was rotten and South Africa was rotten.

Otherwise level-headed people began insulting each other. A South African cabinet minister, Lulu Xingwana, told an interviewer that Afrikaner men were raised to believe women and children were their property and thus theirs to kill. She recanted and apologised the following day. When a leading social scientist, Professor Rachel Jewkes, said an overwhelming number of the black men she had surveyed aspired to sleep with many women, the former editor of the Sunday Times, Mondli Makhanya, denounced her as a racist. Tempers flared. The country’s fuse shortened by the hour.

On one level, South Africa’s response to Steenkamp’s killing was insane. As ferociously as we may love or hate him, Oscar is a stranger to us. We do not know what his love of fast cars and speedboats means. Nor do we know why he so enjoys shooting guns. Most importantly, we do not know why he killed Steenkamp, and we probably never will. We can imagine and reimagine that moment as often and as fiercely as we like. We were not there. All we know is that he shot her through a closed bathroom door. The rest we are making up.

Even if we could know Oscar, what might the state of his being tell us about South Africa? If he was indeed murderously crazy, why should this make all South African men so?

And yet, on another level, South Africa’s over-involved relationship with Oscar makes the profoundest sense. To an uncanny extent, the story the country tells about him is precisely the story it likes to tell about itself. It is no wonder that the two have become confused.

As an infant, Oscar lost his legs. He not only went on to walk, and then to run, but he did so faster than the able-bodied. He appeared to have broken the barriers of human limitation. There was no accounting for him.

So with South Africa. Under apartheid, our souls were rotting. Many people were jailed, tortured and murdered by men in uniform. Street crowds threw tyres around people’s necks and torched them alive on the wisp of an accusation. Ours was a country sick with rancour. It was expected to implode.

In 1994, as if by a miracle, we were reborn. Our capacity to make peace was celebrated the world over. Our president was the most-loved human being on Earth. The sun shone on us. The world marvelled at us. Legless, we had also sprinted faster than anyone. And so, when Oscar came along, we grabbed him and owned him. Oscar was South Africa and South Africa was Oscar. Our stories were the same.

This is an edited extract from an article that first appeared in the Guardian

- Little Liberia is published by Jonathan Ball

- Jonathan Ball home

- Jonathan Ball @ Books LIVE

Book details

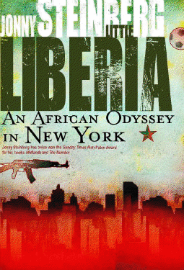

- Little Liberia: An African Odyssey in New York by Jonny Steinberg

Book homepage

EAN: 9781868423828

Find this book with BOOK Finder!

eBook options – Download now!

-

eBook: Little Liberia: An African Odyssey in New York by Jonny Steinberg

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![LWB]()

eBook type: ePub

EAN: 9781868424368

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![ePub]() Download this eBook at LittleWhiteBakkie.com

Download this eBook at LittleWhiteBakkie.com